A Book in Everyone

- Authors Reach

- Apr 22, 2021

- 4 min read

Robin Driscoll discusses his writing journey and shares some perceptive advice

Twenty-something years into writing television and film scripts, I thought I’d have a crack at writing ‘the novel’. Why not? I thought. Everyone’s got a book in them, right?

I’d worked for the likes of Alas Smith & Jones and Mr. Bean, among others, during which time I managed to get the film company, Working Title, to commission a film from me, It was to be called ‘The Blue Tailed Falcon’, a mystery thriller with funny bits, and I was extremely disappointed when, like so many, the film didn’t make it to the screen.

One of the producers suggested that it might work better as a book, but I’d stopped listening by then as I’ve always found it difficult to listen and sulk at the same time.

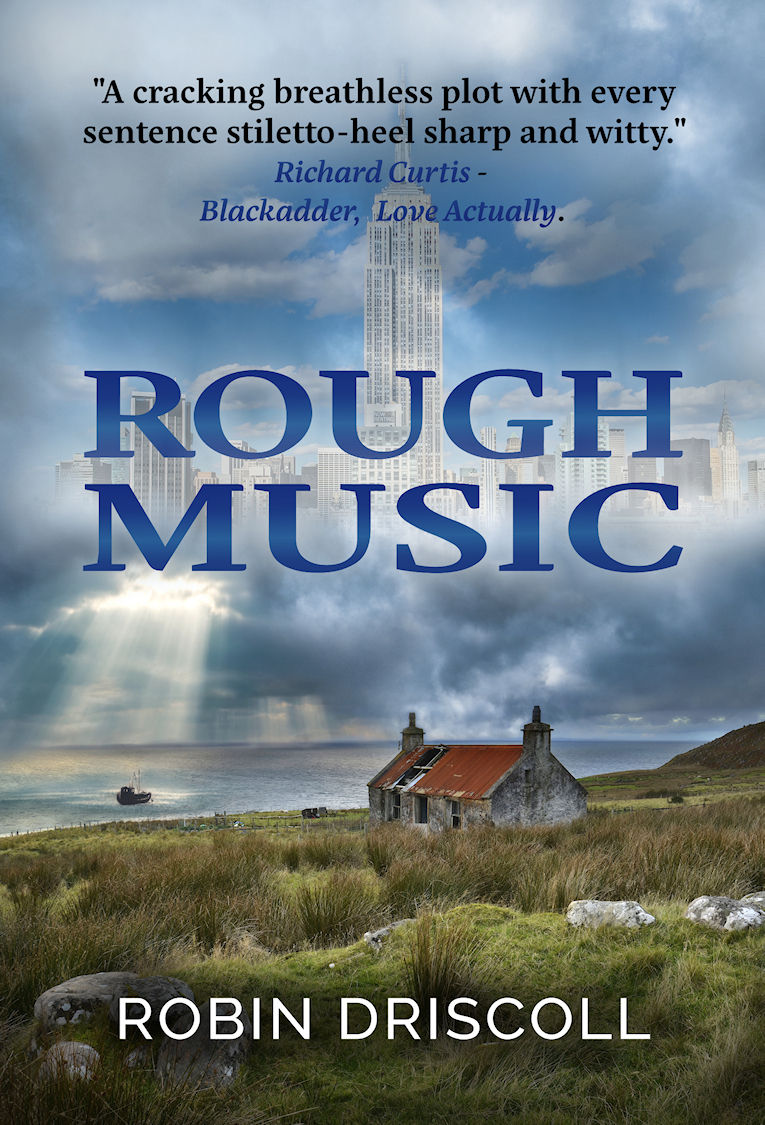

It was several years before I finally took the suggestion and wrote seven chapters of a book version, renaming it ‘Rough Music’. I thought the snappier title looked good written down, especially on the cover of my, soon to be, bestselling blockbuster.

As I discovered early, writing a novel is a world away from writing a screenplay, and I hadn’t really written proper prose since leaving school. Nevertheless, I waded in with my size twelves while inwardly rehearsing my acceptance speech for the Golden Dagger Awards. I sent my first seven chapters to Steve Jeanes, a writer friend of mine in Brighton, anticipating humongous praise and cries for me to publish! I was therefore rather miffed at his emailed response: “You can’t write!”

So, that afternoon, armed with a battery of expletives, I mentally dragged my trophy cabinet (not a burdensome task) to The Open House pub in Brighton’s Preston Park.

“Honest, mate, ya can’t write,” repeated Steve when I joined him at his table. I could’ve been wrong, but he’d sounded rather pleased about it. While he was getting drinks, I stewed for a bit and shredded a half-dozen beer mats.

Then, once seated and before he could utter a word, I listed my writing achievements to date, concluding nicely, I thought, with the fact that Mr. Bean sold and continues to sell to practically every country in the world. I understood story structure, I told him, I understood character development. I had attended Robert McKee’s lectures on ‘Story’. Twice! And John Truby’s course, ‘The 22 Steps of Screenwriting.’ Not to mention Jurgen Wolf’s sitcom lecture and workshop. I had the skills, I told him, I had the tools. I’d worked in the storytelling business for most of my life!

Steve took a thoughtful sip of his Guinness before proving his case in under ten minutes. I’d made the basic mistakes of a first-time writer, he pointed out. And, bum, if he wasn’t right. He’d spotted several blunders in those first seven chapters but here are just two of them: ‘Point of view.’ I was telling the story through two characters in the same ‘scene’ at the same time. Or ‘Double-heading’, as another writer friend of mine calls it.

‘John wondered if she’d noticed his tie. She had, remembering how he’d worn it on their first date.’

At first glance the sentence seems okay, but through who’s eyes are we seeing the scene? His or hers?

Another one: ‘Show don’t tell’, meaning, don’t say it happened. Let the reader see it happen. The author’s voice should remain hidden, letting the characters tell the story. After all, you wouldn’t expect to see a playwright standing on the stage and getting in the way of his actors. Would you?

Here is the author ‘telling’: ‘The warm, sunny day found her lying on her side in the boat.

She stirred on the uncomfortable wooden deck.’

And now ‘showing’: ‘She felt the sun’s warmth on her eyelids as she stirred, the boat’s uneven deck pressing hard into her side.’

I’d been guilty of these gaffs and a truckload of others and, as an avid reader from childhood, was shocked not to have noticed the ‘smoke and mirrors’ authors employ in their craft. As readers, we’re not meant to notice these elements, though their absence can often prevent us from feeling fully engaged with the story or its characters.

After Steve’s rap on the knuckles, I spent a year doing what I should’ve done at the start. And that was to learn about writing fiction. Although I’d spent several years making a living with words, I had to go back to school, because even a qualified plumber doesn’t install central heating in his own home without learning to do it first.

When I finally returned to ‘Rough Music’, I completely rewrote those first chapters. Scriptwriting has taught me that it’s better and far easier to rewrite something than it is to fix it.

Aged 64 at the time of writing this, I still have much to learn. But if there’s one piece of advice I could offer someone starting out, it’s this: If you’ve got a story in your head busting to get out, by all means start getting it down on paper, but read about writing as you go. Learn on the hoof, so to speak. I did just that and found the learning process helped my confidence and motivation to write - each process fueling the other, throwing up fresh ideas and giving me the confidence to push right on to the end of the first draft.

So, is there a book in everyone? was the question, and I think there is. Though, whatever your story’s about, there’s a much better chance of it getting written if you take the time to learn a little about the process. To that end, there are plenty of accessible books out there, whatever genre you’re into. There’s also likely to be a creative writing course available to you locally and loads of free stuff online. So, no excuses. It’s time to get scribbling!

With many thanks to Robin Driscoll for writing this article

Every professional has a distinct journey worth sharing, and this piece masterfully conveys the idea that everyone has a narrative worth telling. Giving a clear presentation of your experience is essential in professions like architecture. The best method to showcase your technical abilities, design experience, and creative initiatives is through architecture CV writing.

What a fantastic topic! “A Book in Everyone” really strikes a chord—just as every idea deserves a spotlight, every thesis deserves its moment of recognition. That’s where professional thesis journal publication services come in; they play a crucial role in transforming research into published work that can be shared with the world.

Super post, Robin, with lots of good advice. It's very interesting to see how you persevered, and weren't put off by initial setbacks. I think that's what makes the difference. The techniques can always be learned, if the will is there.